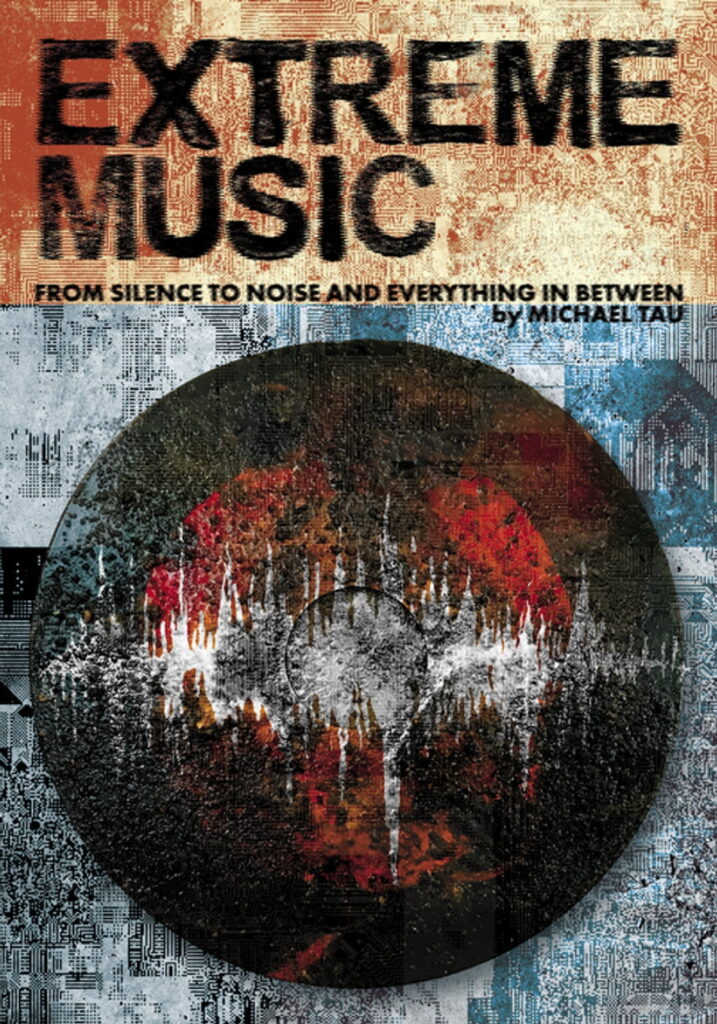

Psychiatrist and music writer Michael Tau has written a new book called Extreme Music. From Silence To Noise And Everything In Between, out now via Feral House. It tackles extreme music formats of all kind, and he is here to walk us through it.

Let’s first start by who you are for those who don’t know you.

I’m a psychiatrist by day, and I also write about music. I wrote reviews, articles, and interviews for different zines and websites for many years. Over the past six years, I took my time writing this book, Extreme Music, which is now published.

On a usual day, I may listen to the Beatles for one second and then switch to Swans or Throbbing Gristle the next. What is your usual daily streaming routine like?

Much like yourself. My music taste can be pretty all over the place. I really like learning about music history, including the traditional part of it, like The Beatles and the classic rock history, but also -and especially- the history of the underground music scenes. On a given day, it can be anything from extreme metal to 60’s psych music. I have a soft spot for early 90’s post-hardcore. Could also be called indie rock. That’s something I tend to listen to a little bit more than the other genres, but I’m all over the map. Anything. Easy listening. Exotica. Grindcore. You name it.

Your book follows extreme music in extreme detail. Before we go into that, I want to know, what was your earliest memory of being exposed to extreme music?

Great question. When I was young, 11 maybe, I used to listen to the radio. There was this radio station called Energy 108. A dance music station. This would have been in the ’90s. Retrospectively, I think it was mainly things we would call Eurodance at this point. That pop-oriented, house-y music from the mid-90s. Then I discovered artists like Aphex Twin and Squarepusher. Probably through music magazines and the early internet. I thought, “Oh, there are more extreme forms of electronic music,” where the beats are extremely fast like happy hardcore or gabber. I remember buying an Atari Teenage Riot CD because I think I had discovered that was some of the fastest music. I was interested in the question “What does music sound like when it is taken to its extreme form?” Through similar processes, I discovered noise and heavy metal. I don’t think that I understood more obscure forms of metal at that age, but I discovered noise, which is a loud and extreme form of music. Of course, as time went on, my understanding of these things became more sophisticated. That’s the core of the book: “What happens when you take a musical concept and you drive it to its most extreme?”

How did you organize working with the material you worked on in this book, and was there material you excluded from the final version of the book?

How I started doing it was that I had a folder on my computer, and I had a bunch of Doc files. So I would create a Doc file for each of the concepts I wanted to explore. I had a Doc file for fast music, and another for loud music, quiet music, large records, and small records. As time moved on, I figured things out and decided where things fit best. Eventually, those Doc files split into smaller Doc files and developed subsections. I guess that’s kind of boring to hear, but that was the physical process and took six years. (laughs)

There were a few casualties. Few things that I started and then realized didn’t make sense in the book. I have a chapter on “Found Music”, and I originally would have included a chapter on “Plunderphonics”, which is an extension of found music. Artists like Negativland and People Like Us, who repurposed different snippets of media. The reason I did not include it was mostly the fact that plunderphonics had been written about by other people quite extensively. It seemed a little bit more off to the side than everything else. And it was going to be difficult to talk about it and then not write about music sampling in general. It’s such a broad topic, that one.

Another section that I decided not to include was “Locked Grooves”. Perhaps you know about RRRecords and the locked groove record RRR-100, where there are a hundred locked grooves on one record. You drop the needle wherever, and you’ll get a different sound playing on the loop. That record is not alone, there are other ones produced like that. Some are compilations, some are created by artists. The only reason I did not include those was that I had enough material and I needed to move on. (laughs) I think it was going to be an interesting chapter. If there is ever going to be an extended edition, that would probably be something I follow up on, because it is really cool in terms of an extreme record concept.

I once interviewed Jamie Stewart of Xiu Xiu and he said “When I was a kid, no jock would listen to The Cure, ever. Or no white kid would listen to hip-hop. Now everybody listens to everything.” Your book makes me realize once again that while that is true, there are still taboos in the art of music. Do you think some of the underground subgenres you mention in the book might go mainstream one day?

That’s a really interesting question. Mainstream is constantly born out of different ideas from the underground, and I agree with you that these days there seems to be a broader set of sounds. This is probably related to streaming, algorithmically designed playlists, and stuff, but people listen to a broader set of things than they used to. I think some of the subcultures I talk about are not even genres, but ideas in a sense.

Or subgenres, microgenres even.

Yeah. And I think that some probably land themselves more to be appropriated by the music industry. The obvious ones would be chapters on different types of vaporwave. There is a thriving online vaporwave scene, and lots of small-scale releases have been put together. But the aesthetic of vaporwave is something that has been popularized, and I think appears in popular music to some extent. I don’t know if floppy disk records are going to be a thing, though. (laughs) But somewhat popular bands have had them produced as a novelty item. I don’t know if Harsh Noise Wall will ever appear in the Billboard Top 40 or Hot 100.

I’m thinking of different genres in the book. (laughs) There was that record from The Flaming Lips with blood inside of it and Kesha was part of that, so I guess you never know. Some things landed themselves better than others.

That being said, a cultural phenomenon called black midi apparently can be an inspiration to a band like Black Midi. I find that sort of promising in terms of breaking taboos.

It’s funny, right? Black Midi is a well-recognized band among many people, but I doubt that many people know the origin of that name is a reference to a genre that actually exists. Now when you search Black Midi, all you get is the band, you can’t get anything about the actual music.

For those who haven’t read your book yet, can you name at least three records that blew your mind with their backstory?

That is difficult. (laughs) I’m scanning the table of contents right now. I guess, if I’m trying to name the most extreme records, I’ll just name the ones that influenced this book.

This will seem unextreme when compared to a lot of things in Extreme Music, but Robert Rich’s album Somnium is one. That seven-hour soundscape, the purpose being you play it while you sleep. I remember first hearing about that, which was really surprising. He created that record because back in university, he would perform sleep concerts for seven hours at a time. Unlike those 20-billion year-long music pieces created using technology, this was something that he would produce live. The album was actually a seven-hour performance that he could perform live, right? To me, that was pretty remarkable. I interviewed Robert Rich in a zine well before this book. That got me thinking about the limits of compositions, especially long ones. And incidentally, unlike a lot of long pieces of music, the record Somnium comes highly recommended by me. It is actually quite enjoyable to listen to, and I actually played it as I slept before.

Another one I discovered quite early on was the grindcore and powerviolence compilations on the Slap-a-Ham Records label. These compilations would have tons and tons of tracks by tons of artists on one seven-inch record. I was really taken by this idea of having really short tracks. In comparison, in the noisecore genre, there are many records where you will have 500 tracks on a seven-inch record, but that was just my first discovery of it. I found it remarkable that there were a bunch of different musicians contributing tiny tracks to a compilation. That was an early thing that made me stop and think, “Why would someone create this?” while sort of discovering the whole scene.

For the final one… There is a chapter in the book about “Major Ego Produkt Objekts & Aktions”. This was a discography I discovered on the internet years ago, on their website of all these strange concept releases by this label. One of the releases was just a box of rotten food inside. Another example was a tape that came inside a jam container of jelly. I remember reading about this in the early days of the internet and thinking, “This is ridiculous!” Right? Limited copies of five. Who would buy them? You can’t even play the music. It was just something that I found fascinating early on. It wasn’t until I started putting this book together that I thought, “Maybe I should find the person who created this and ask them what was the story here.” (laughs) It is a chapter in the book, and it is actually really interesting to see the whole world around this record label. That was just one of these experiences where you hear of these really weird things, and go “Wow! What is this? Why does this exist?”

What do you think, in the sense of packaging, is the weirdest piece of music that you own in your collection?

I don’t own the vast majority of the things discussed in the book. I have a large music collection, but from years of reviewing music rather than from extreme records. A lot of these things, on the other hand, are very rare, and I don’t own them.

One thing I do own, and this was discussed in the book, is the box by the experimental music duo Robe. It’s an edition of ten copies. Each one came with a stock of CD-Rs, but they also came with a cigar box they had modified, basically. And inside each copy came some body product from the duo of Adam Cooley and Kyle Willey. My copy came with hair. (laughs) And a paper bag with a burned book inside. And a few other things. But the gross part was the human hair. Other people got toenails, pubic hair… Mine was regular hair. (laughs) I still have the box, the hair got thrown out though. I don’t think it was thrown out by me. Sad to say that the hair is no longer there, but the rest of it is. It was a really strange thing to get in the mail, and this was back when I was reviewing music, so it actually came unsolicited. But I am glad that I didn’t get the toenails or the pubic hair.

How do you preserve a hairpiece anyway?

That’s a good question. I think it would go dry but still exist. Not sure. You have to apply hair oil regularly to keep it fresh.

From the artists still around, is there a name you would love to interview that you haven’t yet?

That is a great question. Again, I wrote this over many years, and early on, I had this feeling that people would not want to talk about these things and would rather keep them cloaked in mystery. As I reached out, I was surprised at how many people got back to me, as well as how gracious and friendly they were. I was really pleased by that. In the chapter on “Mallsoft”, the subgenre of vaporwave that’s meant to evoke the feeling of walking in a mall, one of the artists named Disconscious, who hasn’t been interviewed anywhere and was actually thought to have disappeared, got back. I just wrote through Bandcamp or something. It took a while, but they got back to me and participated in an in-depth interview. I was shocked. Sometimes, I carry the assumption that someone won’t get back to me, so I feel really happy when they do.

I totally get that.

Yeah. Another example of that would be… Well, I know I don’t answer your question right now, but… (both laugh) Is Vomir, the godfather of HNW. He was so incredibly gracious, nice, and open.

As for people who didn’t get back to me, though I don’t know whether they are the ones that I would love to interview the most, Slap-a-Ham Records would be one. I reached out and they did not get back. Who knows? They might just have an outdated email or something like that. I thought that would be a really interesting story to tell because it is a quite unique music scene. I guess, for me, it’s one thing to talk to an artist who was interviewed a million times, but it’s another to talk to those who are creating things on this extreme fringe. There are really strange musical artifacts, and you want to know their story and motivations to exist. Who are the people behind it? You can read a million interviews with Brian Eno or a number of grindcore acts, but to me, it is really interesting to talk about these obscure, esoteric, strange things and discover a story about them that’s not written elsewhere.

That I totally understand. Final question: When you check your streaming platform’s search history, what are the last three songs that pop up?

Let me see. I can pull this up quickly. I might not want to admit it, though.

I listen to a lot of WFMU, The New Jersey free-form radio station. That is the most recent thing I listened to, but let me check my streaming platform.

Looks like last night, as I slept, I listened to a new record by Robert Rich and Luca Formentini. It is a record called For Sundays When It Rains. Very lovely and relaxing ambient plus acoustic guitar.

I don’t know how accurate this is. These may not be the exact last things I listened to. (laughs) But after that comes a book I currently listen to on UK punk in the early 80s. I also listened to the first EP by the punk band Disorder. Recently, I have been really interested in listening to old seven-inch singles. I don’t own them, I’m sure they cost a lot of money, but I was able to find that EP.

The third one The Tired Sounds Of by Stars Of The Lid. Because the book I read before was on the Kranky Records history, it was written by one of the people who ran the label. And the album is just excellent.