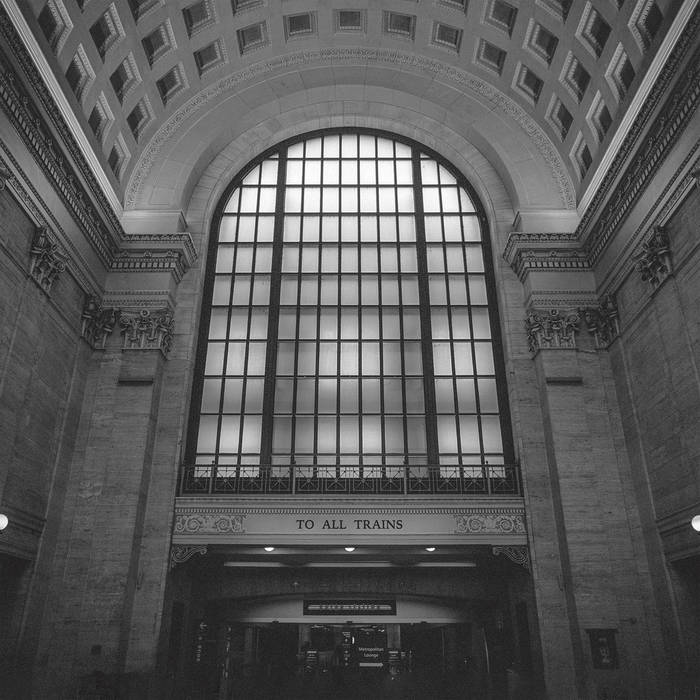

Cover Photo Credit: Daniel Bergeron

Facts: Steve Albini is a living legend of punk and alternative rock -although he doesn’t seem to care about this fact that much. Founder of Shellac; producer of many iconic albums including Nirvana’s In Utero, Pixies’ Surfer Rosa, PJ Harvey’s Rid Of Me, and Dirty Three’s Ocean Songs; Albini is a true rebel, an exception within the context of the capitalist music industry.

We talked to Albini in celebration of the upcoming sixth Shellac studio album, To All Trains. Here is everything that transpired:

Among public transportation, is the train your favorite?

Steve Albini: I very much enjoy using the train when possible. In the US, the train infrastructure is terrible, so there’s not many opportunities to use them, but in Europe and in other countries, the train infrastructure has been modernized along with the rest of the technical infrastructure. It’s possible to take trains as conveniently as anything else. In the US, the entire infrastructure has been designed around cars and individual people owning their cars. So the roadways and the highways are very well developed, but the train and public transportation is not. It’s a nice feature of traveling, though.

How are you with the concept of traveling?

It’s a necessity. Some people romanticize travel because they see more of the world and they meet interesting people. And yes, that’s true. I enjoy that aspect of it. But the allure of traveling has worn very thin for me.

I now only travel when I need to, as an obligation for work or playing with the band. My wife and I sometimes go to Hawaii for vacation, which is great. It’s a beautiful place, and we love being there. We feel very comfortable there. But the traveling part of it, that is going to the airport, sitting on an airplane for hours, that I could do without. I’m not fascinated by all of these little things. (laughs)

You did strike me as more of a home-based guy, a rather settled type.

Well, I like the fact that I have a good studio in Chicago that I can use every day, so I don’t need to travel for work most of the time. And I’m very comfortable here. I have a garden and a cat and a wife and a house, and I’m quite content to do my job at the studio and then go home to them, you know.

Sounds very peaceful. Obviously, the reason why I started off with trains is the album name. Why did you name the upcoming Shellac album To All Trains?

All of us have been to this union station at the photograph on the front cover. The union station in Chicago is a kind of a relic from an era when there were grand public buildings being made. And it’s a beautiful public space, and there are not that many beautiful public spaces anymore. And I like the idea that there is an area for waiting. There’s an area where you’re not doing any commerce, you’re not buying or selling anything, you’re not being entertained, you’re just waiting.

I love that idea. That space where you have to sit and wait would be made beautiful for you as a person, and it’s accessible to everyone. I am kind of nostalgic, I guess, for the idea that there were public places where people, anyone could go and be in the presence of beauty and be in the presence of other people without having to participate in capitalism, without having to enrich anybody. Parks serve the same function, but in Chicago, the parks are very heavily policed, because the people without homes often try to live in the parks. Living there seems, honestly, like a perfectly good use for a park to me. But culturally, there is a tradition of emptying the parks out in the evening. So you can only enjoy a park for certain hours for certain purposes. So it doesn’t have the same function. I just really love that room.

Bob (Weston) is an excellent photographer, and we had the idea that he could take a very nice photograph of this very nice room. I couldn’t be happier with the way the art on the record came out. That photograph really does, you know, does justice to the beauty of that little room.

Chicago recently elected a progressive mayor, right? How do you feel about that?

Yeah, Brandon Johnson. I campaigned for him. I’m not an enormously politically active person. It was the first time in my life when there was an opportunity for me to participate in the campaign of someone with whom I felt a lot of kinship. Chicago has a history of extremely corrupt politics. And the Democratic Party in Chicago has always been a very closed political unit that exerted power externally but was immune to any advice, influence, or opinions from outside. And Brandon Johnson was not part of this central committee, this Chicago machine. He was a grassroots political organizer. He was a teacher. He was involved in the teachers union, which has historically been at odds with the city. When I say the city, I mean the machine politics and the city. I was very much looking forward to being able to vocally support someone that I agreed with in principles. He and I have the same principles for a pluralistic, open society. So I was happy to campaign for him.

Since he’s been elected mayor, it’s been an extremely quiet administration. (laughs) Not a lot has happened, but also not a lot terrible has happened. So it was perhaps idealistic to think that he would be able to make grand changes, but I would rather throw my support behind someone that I agree with fundamentally. Even if practically, they’re going to have a hard time implementing progressive reforms, because I know the reasoning behind every decision is going to be coming from a similar orientation as me. In our system, you’re limited in your choices as to who you can vote for, and it’s not often that you get it.

I’m 61 years old now. I’ve been around for a long time. And in my whole life, there have only been a handful of political people that I could say that person and I are oriented in the same way. Rarely that person and I align politically. Rarely I agree with them and want to support them. Bernie Sanders was one and Brandon Johnson was one. And so when you have these rare opportunities to support someone who thinks almost exactly the way you do, then I feel like it’s worth making the effort to support them.

I would say that Shellac is inherently political, too. With your attitude towards the music industry standards, denying the concept of having to tour when you release records, not releasing singles, not promoting the records in the usual manner…

There is a capitalistic motive behind almost everything that the industry does as a standard method. The things that they do have changed over time, because the industry has changed. The technological base of the industry has changed. The specific things that the industry does to promote music and to advertise and to try to extract money from the audience have changed, but the motivation behind them has always been capitalism.

If you are not fundamentally a capitalist and I’m not fundamentally a capitalist, then the rationale for doing those things disappears, and then you get to examine them as an act on their own. Do we want to promote ourselves in advertising? I think not. I think it’s insulting to an audience to say, here is something you must listen to. That’s presumptuous and a little bit insulting. Do we want to participate in these promotional events where a bunch of bands play in a meaningless festival for the sake of promoting a radio station or a website or something? I think not. We can let those people promote themselves and we don’t have to participate in their egotism.

You could say that it’s politically motivated, but it’s much more a matter of our comfort. We do things in the way we do because we feel more comfortable doing it that way. When we play concerts, we try to include everybody. We try not to have concerts that are age restricted or are members-only kind of a scenarios. That feels exclusionary, and we don’t want to behave that way. We feel better if we can invite everybody. When we play shows, we try to keep the price of admission reasonable. And in some cases, that is kind of a very difficult argument to make because the people that you’re negotiating with are fundamentally trying to maximize the amount of money that they make, and so they are trying to get the highest ticket price possible, and we’re trying to get the lowest ticket price possible. So there is a tension there, but I don’t see it as political in the broad sense, but I recognize there is a political angle to it. For us, it’s really a matter of our comfort and our peace of mind.

I haven’t heard the upcoming album yet, obviously, and I’m very curious about it. You did this one through four recording sessions across years.

The way the band functions, all of us have jobs and lives that we have to conduct. So the amount of time that we have to work on new music is limited. And so we try to get the maximum use of this limited amount of time. We’ll have one weekend once where we can get together to rehearse or write songs or record or something. Back when the pandemic started, there was a period of nearly two years where we did very, very little.

It’s always difficult for us to find time for the band. So we try to organize the obligations of the band in a way that it disrupts our regular lives as little as possible. So in a year, a normal band might tour for three months or four months. That might be normal for a conventional band. Maybe six months of touring, if they’re very active, maybe nine months if they are extremely popular. For us, it’s three or four weeks, maybe five or six weeks maximum. And that is enough. It’s enough to maintain your balance. It’s enough to maintain your associations with each other, your frame of mind, your identity as a band. It’s not luxurious, but it’s enough.

The same with our records. A conventional band might put an album out every year or every 18 months or something. In our timeframe, in our way of working, sometimes it takes years. This one, because of the pandemic and a lot of other things that slowed down the progress of making the record, took a long time to be released, even after it was finished. So on the calendar, it’s been a long time. But in our mind, emotionally, the way we respond to our things, it’s normal.

In any form of partnership, i’s essential to give each other some space.

Yeah. The band is a beloved thing for us. It means the world to me that I get to play music with Bob and Todd (Trainer). It’s really the most satisfying thing in my life. But I also have a job and a business and employees, and as mentioned, a wife and a garden and cats, and all of those things require my attention.

We’ve been playing for more than 30 years now. The reason the band has survived for so long is that the band has never been an obligation for us. It’s always been an opportunity or a diversion or something that we can do apart from the things that we must do. I have to earn money to make a living, I have to conduct my business. That’s an obligation of mine. And when you have a job, even a very nice job like mine, eventually you resent this obligation. We never wanted to have that relationship with the band. The band has always been a purely gratifying thing.

We can already check out the track listing of the record. And one song that immediately took my attention is the obvious The Fall nod called “How I Wrote How I Wrote Elastic Man (cock & bull).” I know that you’re a big The Fall fan. Can you elaborate on that track more?

Bob had written a song about the process of writing the song. So it was a self referential song. It was about the act of writing itself. At the same time, he was reading an experimental novel called the Cock and Bull. That novel has a similar self referential quality, where you read some part of the text, and then it tells you that you’re going to begin again, because you now know something that you didn’t know when you were first reading the story. This kind of experimental fiction, structural change, is echoed in the song. The Fall song, “How I Wrote Elastic Man”, is kind of amazing, because I have heard from people who claim to know that the song was originally going to be called “How I Wrote Plastic Man”, which was the name of a comic book in England. But Mark E. Smith was a little concerned about copyright infringement or some other legal peril, so he changed it to ‘Elastic Man.’ In the song, because of his diction, it’s impossible to tell if he’s saying ‘plastic’ or ‘elastic.’ You really can’t tell which he’s saying. The title of “How I Wrote Elastic Man” is not necessarily referencing the song, but something else, Plastic Man. So it’s possible that title is about the song itself. It’s possible that the title is about something unrelated, but it could also just be the act of writing the word ‘elastic’ rather than ‘plastic’, because he wrote about Plastic Man and then scratched it out and wrote “Elastic Man.” That’s how he wrote “Elastic Man.” He was concerned about the copyright.

I love that title. I love that song. I suggested to Bob that because his song was self referential, that he called his song “How I Wrote How I Wrote Elastic Man.” But he also wanted to make mention Cock and Bull. So that’s in parentheses. We all like parentheses in songs as well.

I guess you don’t actually sing the titular lyric in the song, then?

Yeah, no. The song titles occasionally confirm some lyrical element in the song, but not always.

I was gonna ask if you did actually sing it to make it obscure whether you’re saying elastic or plastic.

No. That doesn’t appear in the song, unfortunately. It would be nice if there was some equally confusing reference in the song, but there isn’t. I’m sorry.

I saw a YouTube comment on your Nardwar interview from years back, and it reads, “Steve Albini is the Noam Chomsky of punk music, with the same uncanny cadence and everything.” How do you feel about that?

I mean, Noam Chomsky is a very admirable public intellectual. I think the clarity of his thinking and the accuracy of his perception is admirable, but I’ve never tried to pattern my life after him.

I guess I can see where that sentiment comes from. You speak really articulately and pretty precise, almost like an academician of punk and rock of sorts.

I feel like if I am trying to communicate, then I should be clear about what I’m saying.It’s a very simple idea. I do a lot of interviews, as you can imagine, and I like it if what I’m saying is unmistakable. You should leave this interview having no question about what I said in any position, any situation or what my perspective is on something. If there is a cultural expectation that artists are going to be hard to understand, that they’re going to be vague and their motivations are going to be cloudy and that they’re following a muse and it’s not necessarily rational, I don’t subscribe to that. I think being in a band and making music is like anything else. You do it intentionally.

We wrote these songs, we performed them. If anyone is going to be able to talk about them intelligently, it’s going to be us. (laughs) That doesn’t seem like an extreme statement. And if I’m going to speak about something, I prefer to be understood. I prefer not to speak in circles, or to be vague or to avoid answering questions. I prefer to answer them.

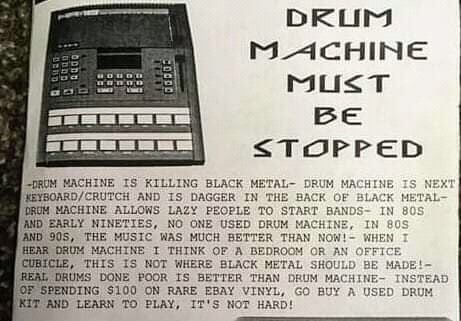

And we all appreciate you doing that. For the next question, I will show you an old photo of a fanzine article piece. You read it first, and then we can talk about it. See below:

(reads and then laughs) Okay.

I know that you’re not a black metal musician or producer. But I think this article shows how much we have come ahead among music communities in general. I interviewed Jamie Stewart from Xiu Xiu a couple of years ago, and he said, “When I was a kid, no jock would listen to The Cure, ever. Or no white kid would listen to hip-hop. Now everybody listens to everything. ” In a similar fashion, the methods of making music actually became more embracing. And you did actually use drum machine in your early records. How do you feel about this piece and what has changed since then?

Reading this little argument is charming to me. I love it when somebody has stakes out of position and they are adamant about it, they are arguing this position with passion. I love that. I don’t have to agree, to appreciate. This person has been driven slightly mad by drum machine, and he is now telling the world about this problem he’s recognized. There’s something about it that I admire. That’s very much in the spirit of the fanzine writing or people who write crazy screeds on and post them in public on telephone poles and things like that. There’s something about this kind of bughouse enthusiasm or mania that I respect. I don’t agree that there’s anything wrong with making music in an office cubicle or in a bedroom. I think making music in a bedroom or an office cubicle is one of the advantages of the modern era. In that it isn’t limited to a guild of official musicians. Anyone can, in their spare time, make music, and that music can allow them to express themselves. I think that’s great and beautiful and should be supported.

This idea that drum machines are somehow evil is obviously a conservative notion. It comes from a retrograde way of thinking that there is only one legitimate kind of music and performance. And my presumption is that this person who wrote this is equally rigid in other parts of their thinking and would be zero fun to hang out with, you know? (laughs) But I can respect that this small irritation in their life has driven them to write this essay. There’s something about it that I think is nice.

I’m glad that you showed me that. It makes me smile because it reminds me of the kind of crazy people that you see arguing with no one at the bus stop. Some of the best writing is from these acts of mania where there is an argument that no one else is participating in, you know?

You are welcome. A friend of mine wants to know one really insane concert memory you have from the eighties.

I went to see Einstürzende Neubauten at a small punk club in Chicago called Exit. They were using power tools and that kind of stuff. At one point, somebody poured something flammable onto the stage. And the stage got caught fire and was burning. Everyone who worked at the club was really concerned and trying to get to the stage to put the fire out. But the band were not concerned at all and just continued playing.

That reminds me of the time when the band Volcano Suns from Boston came to Chicago on their final tour. They had announced that they were breaking up the band. And this is their final tour. They played their final concert in Chicago at a club called Lounge X. I was at the side of the stage, and each of the members of Volcano Suns had someone preparing drinks for them during the show and bringing them drinks. And I was friends with Bob Weston, the bass player. I was his Jagermeister steward. I was making him shots of Jagermeister and bringing them to him.

David Yow from The Jesus Lizard was there at the show, he was torturing the band a little bit. He was taking the flyers from the gig, crumpling them into a ball, setting them on fire with his cigarette lighter and rolling them onto stage like flaming bowling balls. Eventually there were three or four of these flaming balls on stage, and one of them caught the carpeting on fire. The carpeting of the stage was burning while the band was playing. David Yow took it on himself to extinguish the fire by climbing on top of the PA and doing a belly flop onto the burning stage.

Oh my god. (laughs)

I thought that was a beautiful moment of David Yow extinguishing the fire with a belly flop. But it was a fire that he started himself, so it was ultimately his responsibility.

As a really young person, you started off with clarinet. Do you still get along with it?

Yeah, I was nine years old, and I played the clarinet. I haven’t played a clarinet since then. (laughs)

Okay. What about guitar pedals? Do you have a favorite pedal in your collection?

I don’t use that many pedals. I have a Fuzz-Tone that I use in Shellac called the Harmonic Percolator. I’ve had it for many years, and I still use it. It’s the only pedal I really use, honestly.

As a working studio, we have to have a collection of pedals and instruments and amplifiers for people to use. But I don’t really have a favorite one. We have all of them, basically. (laughs)

I talked to Alex Hall from the band Grails a while ago, and he said that nowadays he only uses a multi-effect processor because he has grown sick of pedals.

I can see that as a practical solution if you use a lot of effects, but you don’t want to have a lot of individual pedals. I know some other people are doing similar stuff. I don’t. As a musician, that doesn’t interest me. But if anyone in the studio has a piece of equipment that they rely on, I tend to trust them to choose the right thing.

This one’s a little bit personal, actually, but it may actually connect to our readers as well. I only recently started my attempts to make music. I hadn’t really touched any instrument in my life. I was mostly inclined to write about music, but recently, I discovered a new passion within it. Shortly after the start of my new passion, I actually started a full time job, to which at first I thought this might slow me down a bit, but instead, conversely, it drove me more to that idea. Almost like a rebellious outcry.

I think there is something to be said for the idea that the things that you are passionate about are important in your life, and you make time for them, and they are the most important things in your life. And separate from that, you need to make a living somehow. You need to pay your rent and buy your groceries. There is a kind of a chauvinism in the music community that if you’re not doing music professionally, if that’s not your entire livelihood, then somehow it’s not legitimate. If you pay your rent by being a carpenter or by a waiter or selling cars or something, if that’s your occupation, then the music that you make is somehow less significant than the people who are professional musicians. I don’t subscribe to that theory at all. I know that the music and the shows and the bands that have meant the most to me were not made by people who were professional musicians. They were made by people who were obsessed with music. They would do it at gunpoint. They would still make music. I think that’s the distinction for me, how much does your music mean to you? Does it mean the world to you? Would you fight an army to be able to make this record? Or is it just your occupation? Like, “Yeah, I’m a guitar player. I just. play guitar. That’s my job, you know?”

I don’t see a significant difference between the quality or the intensity of the music that’s made by amateurs and music that’s made by professionals. If anything, I think the music made by professionals is a little less interesting, a little less original, a little less inspirational. So I’ve always said that there is no shame in earning a living. There’s nothing to be self conscious about. If your music is not your livelihood, that doesn’t mean that it’s not the best thing in the world for you.

Thanks for that answer. I hope that people will actually find what you say inspiring, because I do. In an interview from five years ago, you said this: “Nothing excites me.” Is that true to this day?

I think you can tell that I have something of a routine about how I conduct my life, and I don’t look for reasons to be inflamed about things. I don’t look for reasons to be excited. Being in the band is extremely satisfying. Playing music is very satisfying. But in terms of the practice of my job, making records, being in the studio, it’s a job. It’s a good job and very satisfying. I get to witness other people having remarkable moments in their lives, and that’s also very satisfying. But I’m here for a purpose. I’m here to make records for other people. That’s why I’m here. I’m not here for my own entertainment.

And I understand from what you just said that you’re content without the excitement. That’s great.

Yeah. There have been times in my life when things were changing rapidly around me, and there is an excitement to that, but it also creates problems. To the extent that things are exciting, they are also irritating.

I want to ask you a question from an engineering standpoint. I don’t know if you listened to the latest Beatles song “Now and Then.”

I heard it. I didn’t listen carefully, but I heard it. Yeah.

From a production standpoint, to me, it actually sounds confusing because John’s vocals and piano sounds very vintage, very sixties qualitywise, while Ringo’s drumming is very modern. That bugs me a little. I was gonna ask what you think about that.

I feel very strongly about this aspect of music making: Let’s say you, Deniz, have a band. You want to make some music with your band, and you decide to do it in a certain way. That’s your business, and anybody else who has an opinion about it can f.ck off.

I feel that way about this Beatles track. I am not the biggest fan of the Beatles. I admire the Beatles. I think they’re an important group, and some of their music is beautiful. I have no problem with the Beatles, but I’m not in the Beatles. I don’t feel like I should necessarily have an opinion about how the Beatles conduct themselves. I can like their music or not like it. That’s fine, but as for the method of how they do things and what it’s supposed to sound like. That’s not my department. That’s for them.

There is a kind of a notion that musicians have a responsibility to their audience. Like they owe their audience to do things in the way that their audience expects of them. And that’s horseshit. You know? Your band is yours. You can do it however you like.

If you have any recollection of the latest tracks you listened to, can you tell me the last three?

The awkward thing for me is that my job every day is listening to music. So the last three songs I listened to were the the pieces of music that I was working on in the studio for my clients. If I think back to what was the last piece of music that I listened to for pleasure, not as part of my work, I have to think back several days, what my wife was playing in the house when I was hanging around with her. And that was a Tina Turner song: “Mustang Sally.”

Let’s imagine we’re at a Musicians Theme Park 100 years from now, where every artist or band featured have their own memorial stone with a certain lyric by them written on it. Which one of the lyrics would you like to see written on Shellac’s stone?

Wow. (laughs) My instinct is to just completely punt and say I don’t care, because I genuinely don’t care, but I’m also struggling to remember any of our lyrics at the moment.

I actually guessed that you would say exactly that. Still wanted to check.

Yeah. I’m sorry. I can’t give you an answer because I just can’t. I’m drawing a blank thinking of our lyrics, even. I apologize.

On second thought: There’s one in the upcoming Shellac album that you have not heard. There is a song about singing karaoke at a bar. There was a bar in Chicago that would have karaoke nights, and they had a little sign behind the bar that said, “No high fives,” meaning, you’re not supposed to high five people in that bar. Because at the time, that was a very jock-coded thing, and it was used by business people and jerks. The high five as a gesture did not have great connotations at that time.

There was another sign that said, “Except during karaoke night.” So during karaoke, if somebody does a great song when they come off stage, you could give them a high five. That was permissible. And in the song on the new Shellac album about karaoke, at one point, I sing “High five!” A few moments later, this time Bob says “High five!” So if we were to put a lyric on our tombstone, I would hope that it would be me saying “High five” and then Bob saying “High five.”

Would it include caricatures of you, too?

I mean, you’re making the tombstone. You can put whatever you want.

You can check out Shellac’s Bandcamp profile here.